Episode Transcript

[00:00:00] Speaker A: Hi there. Welcome to the Niagara Falls History and Poetry Podcast where I will discuss the history of Niagara Falls and area through the lens of the poetry that has been written about the falls. I am Andrew Porteous, a retired local history librarian who worked at the Niagara Falls Ontario Public Library for almost 30 years. I have been the curator of the Niagara Falls Poetry Project since its inception in 1999. The website is Niagara Poetry Cat, or you can just use your favorite search engine and search for Niagara Falls poetry. My philosophy on the history of Niagara Falls is that if I can't find a poem about it, it didn't happen.

I have been known, though to write the odd limerick about various events so that it did in fact happen.

This podcast is available in audio format wherever you get your podcast from, as well as on YouTube with augmented video features. Also, since long before humankind came to Niagara, it was occupied by animals and amongst those animals were bears.

Very occasionally bears are mentioned in the poetry of Niagara Falls, but curiously I have found two very similar poems about a bear in a canoe, but none about the type of bears that may be found dancing at Peppermints, a male strip club in Niagara Falls, Ontario. If anyone wants to rectify this dreadful admission, please write one and submit it to me. Incidentally, early in my career at the Niagara Falls Public Library, I was a branch manager of the Drummond Branch Library and looking out of the south window I could see the Mintz Peppermints Building next door. Mintz was female dancers, Peppermint was male dancers, and they often had dancers hanging around on the fire escape. Just beyond Mintz was a battlefield, elementary school and playground. Looking out of the north window I could see the Morse and Sons Funeral Home. Looking west was the site of the Battle of Lundy's Lane in the War of 1812, and on the hill above, which had also been part of the battleground, the cemetery where many of the soldiers are buried. I've always thought that it was a weird juxtaposition, a microcosm of small town life.

Anyway, back to the Bears the earliest mention of bears in poetry in Niagara that I found comes from Adam Hood Burwell, known as the pioneer poet who wrote under the pen name Arius. Burwell, who was born in 1790 and spent his childhood in Bertie Township, the present day Fort Erie on the northeastern shore of Lake Erie, went on to become an accomplished poet, essayist and clergyman. In 1822 bur he published the poem Journal of a Day's Journey in Upper Canada in October 1816 in the Montreal Scribbler on this particular day, Burwell had walked from Niagara on the lake to Fort Erie, and darkness was fast approaching as he arrived at home, where his family and his dog Gunner were waiting.

Toward the end of the poem, Burwell wrote, gunnar had call, yet scarce could spare a whistle or a breath of air, and keep him closely by my side. For on his courage I relied bears, wolves and foxes, dreadful foes, and all the formidable train terror could picture on my brain. Whene'er I heard the bushes crack, I thought them bouncing on my back and twitched about my head to see what monster was attacking me.

Burwell was imagining these dangers chasing him, but they were very real dangers then. At that time there was still a lot of wilderness area in the Niagara Peninsula, and it was still known as a far western area of Upper and lower Canada.

In 1897, Charles Edward Jaque published the poem Laura Secord about the famous walk Laura Secord took to warn the British troops about an American attack on their outpost at Beaver Dams. In it, he states that from within the wild recesses of the tangled wildernesses sounds mysterious pursued her along the winding forest way, and she heard the guttural growling of the bears that near her prowling crush their course through coverts, gloomy with their cubs in noisy play.

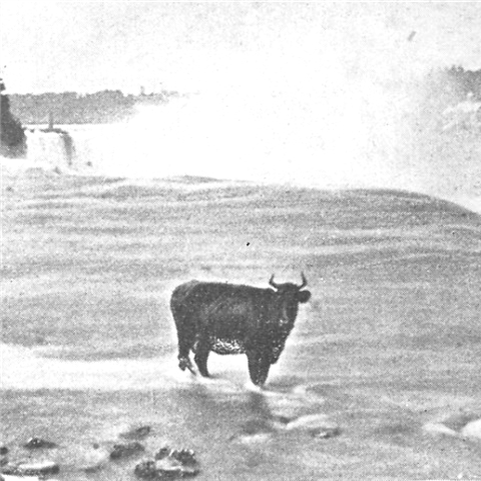

There are other instances of bears in the falls area, including one shot in the small community of Fallsview in 1920 in Niagara Falls, Ontario, a picture of which is added to the YouTube version of this podcast. In 2017, a bear was shot plundering garbage cans in the small community of Amherst, New York, just a few kilometres south of Niagara Falls.

One interesting postcard from 1907 shows the Cracker Jack bears one going over the falls in a large crackerjack box while eating a box of crackerjack and he had a life preserver hanging around one of his arms. The other bearer is standing on a ladder attached to an airship and is holding a rope attached to the life preserver ring. Now, this is six years after Anna Edson Taylor became the first person to go over the falls in a barrel.

Anyway, to finally get to the incident that is the subject of Today's episode, in 1872 George Holly published a guidebook which was republished in various guises until 1883.

In it he includes the story of a bear getting into a canoe with a fisherman near Navy island, just upstream of the rapids leading to Niagara Falls. The YouTube version of this podcast shows two drawings of this incident. In the first, from 1872, the fisherman is at the stern of the canoe, whilst the bears sitting placidly in the bow. In the 1883 version, the bear is roaring aggressively at the fisherman, making for a much more dynamic image. Holly's prose piece paints a vivid picture of this interaction. Soon after The War of 1812, a fisherman whose name we will call Fisher on a certain day went out upon the river about three miles above the falls, and while anchored and fishing from his canoe, he saw a bear in the water, making very leisurely for Navy Island. Not understanding very thoroughly the nature and habits of the animal, Thinking he would be a capital prize, and having a spear in the canoe, he hoisted anchor and started in pursuit. As the canoe drew near, the bear turned to pay his respects to its occupant. Fisher, with his spear, made a desperate thrust at him, quicker and more deftly than the most expert fencer could have done. The quadruped parried the blow and, disarming his assailant, knocked the spear more than 10ft from the canoe. Fisher then seized the paddle and belabored the bear over his head and on his paws. As he placed the latter on the side of the canoe and drew himself in, the now frightened fisherman, not knowing how to swim, was in a most uncomfortable quandary when the animal deliberately sat himself down, facing him in the bow of the canoe. Resolving in his own mind that he would generously resign the whole canoe to the creature as soon as he could reach the land, he raised his paddle and began to pull vigorously shoreward, especially as the rapids lay just below him and the falls were roaring most ominously.

But much to his surprise, as soon as he began to paddle, Bruin began to growl, and as he repeated his stroke, the occupant of the bough raised his note of disapproval an octave higher, and at the same time made a motion as if he would go for him.

Fisher had no desire to cultivate a closer intimacy, and so stopped battling. Bruin then serenely contemplated the landscape in the direction of the island. Fisher was also intensely interested in the same scene, still more intensely impressed with their constant and and insidious approach to the rapids, but most of all, exercise as to the manner of his own escape, he tried the paddle again, but the tyrant of the quarterdeck again emphatically objected. And as he was master of the situation and fully resolved not to resign the command of that craft until the termination of the voyage, there was no alternative but submission.

Still, the rapids were frightful in the air, and something must be done. He gave a tremendous shout, but Bruin was not in a musical mood, and vetoed that with as much emphasis as he had done the paddling. Then he turned his eyes on Fisher quite interestedly, as if he was calculating the best method of dissecting him. The situation was fast becoming something more than painful.

Madame Bear in opposite ends of the canoe, floating not exactly double, but together, to inevitable destruction. But every suspense has an end. The single shout, or something else, had called the attention of the neighbors to the canoe. They came to the rescue, and an old settler, with a musket, which he had used in the war, insinuated a charge of buckshot into Bruin's internal arrangements, which induced him to take to the water, after which he was soon taken captive and dead to the shore. He weighed over 300 pounds anyway. In 1861, a decade before Halley's account, the poet Florio, which was a pseudonym often used by Clement Clarke Moore, published the poem A Legend of Niagara, describing the same incident, but with a native fisherman rather than a settler. Fisherman Murr was the author of A Night Before Christmas, the beloved poem in which Santa's reindeers are first named.

So a legend of Niagara by Florio.

An Indian in the days of yore of fish and fur's abounding store, Would cross Niagara stream, Just where the river, smooth and wide, pours towards the gulf, its treacherous tide like some distant deceitful dream.

Nearby a bear was crossing too, whose head no sooner rose to view than straight the brave urged his canoe to grasp an easy prey. But Bruin fled, not glad to greet a resting place for weary feet, he turned and swam his foot of meat upon the watery way they met the paddle's blow was dealt with paw received, or scarcely felt by fur protected bear, who, reaching up as for a bough, Climbed gracefully into the prow and sat serenely there. The astonished brave sought in his turn the ultima thule of the stern, and then sat down to stare. And thus, in armed neutrality they sat in thoughtful vis a vis, While the bank drifted silently to meet the breaker's wight.

But when the Indian seized an oar to stay his course or seek the shore, Admonish'd by an ominous roar, he dropp'd it in affright. For in those cavern'rous jaws he sees molars, incisors, cuspides, Enough of a hero's heart to freeze, or dentist to delight. More dreadful still, the angry thaw, like some huge monster, seem'd to call, impatient for its prey, and shows its breaker's flashing teeth to welcome him to depths beneath and breathe his breath of spray.

Visions of fire and frying pan encompass that bewildered man, the watery furies oppressed, and Shakespeare's thought his bosom fills. Better to bear our present ills than fly. You know the rest, Whether the brave prove dainty fair, and then the foul devour the bear, Though unto them the loss was sair to us is less to do, but still arrayed in fancy's gleam, have floated down tradition's stream the twain in that canoe and furnish to the faces pale the matter to adorn our tale and point of moral too.

We float upon life's lasting tide, While towards some gulf the waters glide with unremitting might.

We float upon life's lasting tide, While towards some gulf the waters glide with unremitting might, and some black bear holds us in awe. Like the black care which Horace saw behind the Roman night we fain would cease an o'er to reach some sylvan shore, some silvery breach. But still the moment miss for pride or ease, or care or fear, Sits with overwhelming presence near the saving hand we dare not lift, and gently thus we drift, drift, drift into the dread abyss.

Our land, which boasts that it prepares its moral and material wares, should make its legends too, and mixing one of native Clare, let's drop a lion's in the way, and instead hereafter say a bear's in the canoe.

Now Florio assumes that the reader will be aware of his lips literary references, as all well educated Victorians surely were, referencing Hamlet's to be or not to be soliloquy, and also assumes that the native fisherman knows it too, which is less probable. The part Floriol was referencing reads no traply, returns, puzzles, will, and makes us rather bear those ills we have than fly to others that we know not of.

Florio also references Horace's ode Black Care, sits aboard the bronze plated trireme, and sits behind the knight with black hair, being the constant worry and anxiety that we often feel. And Florio wants to replace John Newton's poem Him the Sluggard, referencing excuses for not doing things.

At every poor excuse they catch are lions in the way, with bears in the canoe.

Now, in 1889, James MacIntyre published a collection of his poetic works in which a version of these events is told in the poem Bear and Falls. It possibly had been published earlier, although I've not run across it anywhere else. MacIntyre had been named by notive literary critic and theorist William Arthur Deakin in his book The Four James's, published in 1927. According to the book's description, it is a humorous and affectionate tribute to the four worst poets of Canada. Writing in English so James McIntyre bear and falls Strange incidents do happen ever on the famed Niagara river. This thought to mind it now recalls event Three miles above the falls thrilling ventures there abound A bear which weighed 800 pounds hunters they do him discover as he was swimming down the river they felt he would be glorious prize this grand fat bear of mighty size Three men they jumped into canoe A skilful and determined crew soon alongside of him they row, but kindly feelings he doth show Quick he scrambled o'er the boat side for to enjoy a good boat ride and as o'er the side he straddles, they hit him on the head with paddles, but all in vain. So two of crew a short time bade the bear adieu and soon they swiftly swam to shore. But current down the river bore man, bear and boat the sound appalls of roaring mighty waterfalls but vigorous now he plies the oar in hopes to save safely reach the shore. But this may bear to grin and growl and wear on brow a horrid scowl so poor a man sore against his will finds it in boat he must keep still or else be hugged to death by bear While sound of falls becomes more near. But his two friends so brave and true, Row quick longside in a canoe and fire in bruin leaden balls this saving friend from bear and fox falls. Yeah. So here we have in a prose piece and two poems about an absolutely unbelievable event that occurs on the Niagara river just above the falls. In two versions, the bear is killed by hunters who come to the rescue, but in Moore's version, both go drifting over the falls, allowing the poem and the event to be transformed into into a morality tale ending where one is unable to lift a hand to save oneself. Because in this case of fear, Holly maintained that the bear weighed over 300 pounds, while McIntyre claims that it weighs 800 pounds. Adult black bears apparently weigh in at between 90 and 500 pounds, depending on the age and sex. I also weigh in between 90 and 500 pounds and have managed to get myself back into a canoe that was floating on a river, and it's no easy feat, even without people pummeling me with their paddles. So to think that a bear would be able to do so tests the outer limits of believability.

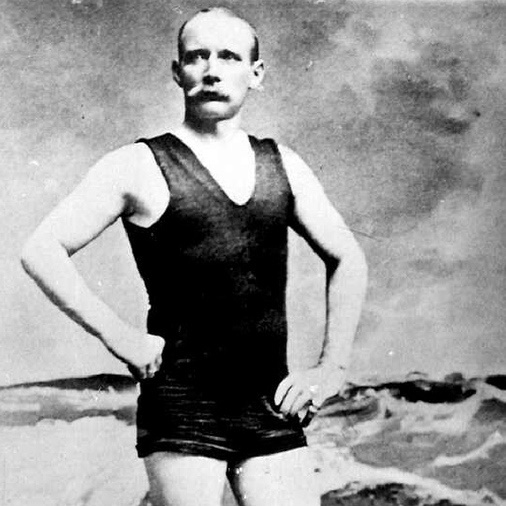

Anyway, thank you for listening to this podcast. If you enjoy it, please hit the like button and subscribe to be notified of future podcasts and please share it amongst your friends. See you next time, when I will be talking about the incredible adventures of Captain Matthew Webb and the first person to swim the English Channel and his untimely demise at Niagara.

[00:18:06] Speaker B: Sa Sa Sa Sa Sa Sa sa.

[00:21:14] Speaker A: Read by Andrew Porteous.

Read by Andrew Porteous.